Kings MountainAnd The Over-Mountain Men

From the West they came over the mountains, that 28th day of September 1780, in snow "shoe mouth deep," a mounted column of Carolinians and Virginians, one thousand strong, in hunting shirts and leggings, knives at their belts and the slender rifles of the frontier across their saddles. They came full of wrath, seeking their adversary of the summer past, British Maj. Patrick Ferguson and his Loyalist battalion, and this time they came to battle him to the finish. These "over-mountain" men hailed from the fertile valleys west of the Alleghenies, around the headwaters of the rivers Watauga, Holston, and Nolichucky, where a few years before they had established little settlements, remote and all but completely independent of the Royal authority in the eastern colonies. They were of Irish, Scotch, Welsh, English, French, and German ancestry, but most were hardy, diligent Scotch-Irish hunters, small farmers, herdsmen, and artisans. They had been little threatened by the war of the American Revolution, now 5 years old, until England, fought to a stalemate in the northern colonies, had turned her military strategy toward conquest of the South. Following the surrender of a huge American army at Charleston, S.C., in May 1780, British Gen. Charles Cornwallis had easily overrun the entire state. Inhabitants of all political persuasions flocked by hundreds to pledge fealty to the Crown: dyed-in-the-wool Loyalists; repentant Whigs who now doubted the wisdom of their rebellion against the King's government; and even many staunch Whigs who took protection to save life and property. To embody these avowed Loyalists into a strong royal militia, Cornwallis ordered Major Ferguson to range the country between the Catawba and Saluda Rivers. Ferguson, son of a Scottish judge, was a professional soldier who had entered the British service at age 15. A renowned marksman, inventor of an improved breech-loading rifle, and 3-year veteran of this war, he had come to South Carolina in command of a regiment of American Loyalists recruited in New York and New Jersey. Upon the surrender of Charleston, he had been appointed Major Commandant of all the Loyalist militia that might be raised in the Carolinas. Although slight of build, with a long oval, gentle-looking face and an affable disposition, he was called by his officers "Bull Dog." Within days of his invasion of the South Carolina upcountry, Ferguson had succeeded in recruiting several thousand Carolinians of loyal British persuasion. With them he began to hunt down and punish "rebels" who continued to resist Royal authority. There ensued on the frontier the same kind of murderous, confused guerrilla warfare as in the east and the piedmont, where hundreds of stubborn Whigs were harassing British and Loyalist forces. During the summer, as Ferguson marched and counter-marched through the Carolina upcountry, militia regiments of over-mountain men swept eastward across the ranges and engaged him or his detachments in fierce little actions at places with names like Wofford's Iron Works, Musgrove's Mill, Thicketty Fort, and Cedar Spring. But in August, after another American Continental Army from the north suffered a crushing defeat by Cornwallis at Camden, the over-mountain men retired home to rest and to strengthen their forces, resolving to recross the mountains when able to have another go at Ferguson.

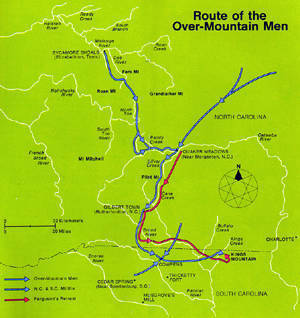

As they tarried at home, keeping a watch to the eastward, Cornwallis mounted an invasion of North Carolina. From the outset of the British Southern campaign, it had been His Lordship's firm conviction that the only justification for such a campaign was to carry the war into Virginia. In September, he took up a march for Charlotte, the first step toward the base he hoped to form at Hillsborough with the aid of North Carolina Loyalists. To protect his left flank from guerrilla attack and to enlist still more Loyalists, he ordered Ferguson to move northward Into western North Carolina before joining the main army when it reached Charlotte. In late September 1780, Ferguson took up post at Gilbert Town, a hamlet of one house and several outbuildings a few miles from the mountains. From here he dispatched a paroled Whig prisoner to Col. Isaac Shelby, whom he considered the titular head of the "backwater men," as he chose to call them. The messenger was charged with threatening the Westerners that "if they did not desist from their opposition to the British arms, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword." It was a challenge not to be ignored. On September 25, 1780, the over-mountain men began to gather under Colonels Charles McDowell, John Sevier, Isaac Shelby, and William Campbell at Sycamore Shoals, on the Watauga. Early the next day they began an arduous march through the snow-covered mountains that brought them in 5 days to the warmer clime of Quaker Meadows on the Catawba, where 350 more frontiersmen under Benjamin Cleveland and Joseph Winston joined them. As the little volunteer army marched southwestward around Pilot Mountain toward Gilbert Town, Ferguson's spies brought him word that the over-mountain men were advancing against him. Upon learning of their approach, Ferguson, who had tarried too long at Gilbert Town hoping to intercept another rebel force which was retreating northward, began to call in reinforcements and fade back toward the protection of Cornwallis' main army. On October 1, he issued a dramatic broad-side, appealing to loyal North Carolinians to "run to camp" to save themselves from the "back water men. . . a set of mongrels." Then he continued eastward until, on the afternoon of October 6, he reached Kings Mountain, just south of the North Carolina border, where he decided to encamp and await his foe. Kings Mountain is a rocky, wooded, outlying spur of the Blue Ridge, rising some 60 feet above the plain around it. A plateau at its summit, about 600 yards long and 70 feet wide at one end and 120 at the other, gave Ferguson a seemingly excellent campsite and defensive position for his 1,100 men. When the over-mountain men reached Gilbert Town and discovered that their quarry had flown, Shelby reported later, "it was determined. . .to pursue him unremittingly with as many of our troops as could be well armed and well mounted, leaving the weak horses and footmen to follow as fast as they could." At the Cowpens on the 6th, some 400 South Carolinians under Colonels James Williams, William Hill, and Edward Lacey joined them. Ferguson's trail had been hard to follow, but here they learned positively that he was some 30 miles ahead in the vicinity of Kings Mountain. Through a night of pouring rain and all the next day in intermittent showers, they pushed on. It was after noon, Saturday, October 7, when they arrived at the mountain in a misty rain. They dismounted, fastened their coats and blankets on their saddles, tied their horses, and formed in a horseshoe around the base of the mountain behind their mounted leaders. The Loyalists were taken totally by surprise. About 3 o'clock as the Whigs began to encircle the mountain, Ferguson's pickets found them and skirmished briefly. Campbell's regiment on the southeastern and Shelby's on the northwestern slope simultaneously opened the engagement. From the crest the Loyalists rained down a volley fire, but the densely wooded sides of the mountain provided the attackers with good cover. One of them later recalled that he "took right up the side of the mountain and fought from tree to tree. . . to the summit." As the two Whig regiments neared Ferguson's lines, the Loyalists charged with the bayonet and drove them down. Twice Campbell's and Shelby's men were driven down the slope by Loyalist muskets and bayonets before attacks on the Loyalists from other Whig regiments enabled them to push to the summit. To one of the attackers, the mountain appeared "volcanic; there flashed along its summit, and around its base, and up its sides, one long sulphurous blaze." Over the vicious crack of rifles and the shouts and crashing of men through the brush there sounded continually the shrill call of the silver whistle with which Patrick Ferguson maneuvered his men. Cruelly punishing an agile horse, he was everywhere, a conspicuous target in a checkered hunting shirt, with his great silver whistle in his teeth. Suddenly, he fell from his horse, one foot hanging in a stirrup and several bullets in his body. His men propped him against a tree, where he died. And his second-in-command ordered a white flag hoisted. The fight had "continued warm for an hour," and despite Loyalist cries of surrender, the Whig commanders could not immediately restrain their men, who continued to shoot down the terrified, disordered enemy. For some time American Whigs slew American Tories: Ferguson had been the only British soldier on either side of the relentless battle. The "back water men," whom Ferguson had scorned, had slain 225 Loyalists, wounded 163, and taken 716 prisoners, with a loss to themselves of 28 killed and 62 wounded. The aftermath of the battle was cruel and gruesome. The autumn darkness descended swiftly. The victors, one of them wrote, "had to encamp on the ground with the dead and wounded, and pass the night amid groans and lamentations." "The groans of the wounded and dying on the mountain," said another, "were truly affecting-begging piteously for a little water; but in the hurry, confusion and exhaustion of the Whigs, these cries, when emanating from the Tories, were little heeded." And worse was in store. The next morning the sun came out for the first time in several days. The Whigs were eager to be on the march home for fear that Cornwallis would send a force in pursuit of them. So the dead were carelessly buried in piles under old logs and rocks, the wounded tended, the plunder divided. Many Whigs simply walked off, but a strong force marched northward with the prisoners to turn them over to Continental Army jurisdiction at Hillsborough, N.C. On this doleful journey a number of the prisoners were beaten brutally and some hacked with swords. And the fury that had driven the Whigs to continue firing on the surrendered Loyalists on the mountain inspired unjustified murder of a number of them. In a final outrage a week later, when the army reached the Bickerstaff settlement some 50 miles from the field of battle, a committee of Whig colonels appointed themselves a jury to try some of the "obnoxious" Loyalists. In an all-day, outdoor trial in the rain, 36 were found guilty of "breaking open houses, killing the men, turning the men and women out of doors, and burning the houses." The trial was concluded after dark, and nine of the convicted were "swung off." Once the surviving prisoners were delivered, the army from beyond the mountains faded away as quickly and quietly as it had gathered. But its achievement was substantial. As news of the victory spread through the region, Whig spirits revived as Loyalist spirits drooped. Whig militiamen began turning out in North Carolina and Virginia, while Loyalists, upon whom Cornwallis depended heavily for support, lost courage and refused to enlist. Cornwallis himself, on learning at Charlotte of Ferguson's defeat, feared that the Whigs, whose strength he exaggerated, might seize his posts at Camden and Ninety-Six. So heavily did Ferguson's fate weigh upon the British commander that a week after Kings Mountain he began a hurried, wretched retreat southward to an encampment at Winnsboro between his two posts. The victory of the over-mountain men ultimately delayed Cornwallis' plan for 3 months, during which the Continental Army organized a new offensive in the South. At Charlotte, in December 1780, Gen. Nathaniel Greene replaced Gen. Horatio Gates as Continental Army commander of the Southern Department and seized from Cornwallis the military initiative in the Carolinas, an initiative the British general never regained before he was forced to surrender at Yorktown in Virginia on October 19, 1781. Kings Mountain thus became Cornwallis' first misstep toward the defeat that marked the end of a long and bitter war.

George F. Scheer

|